Artist statement

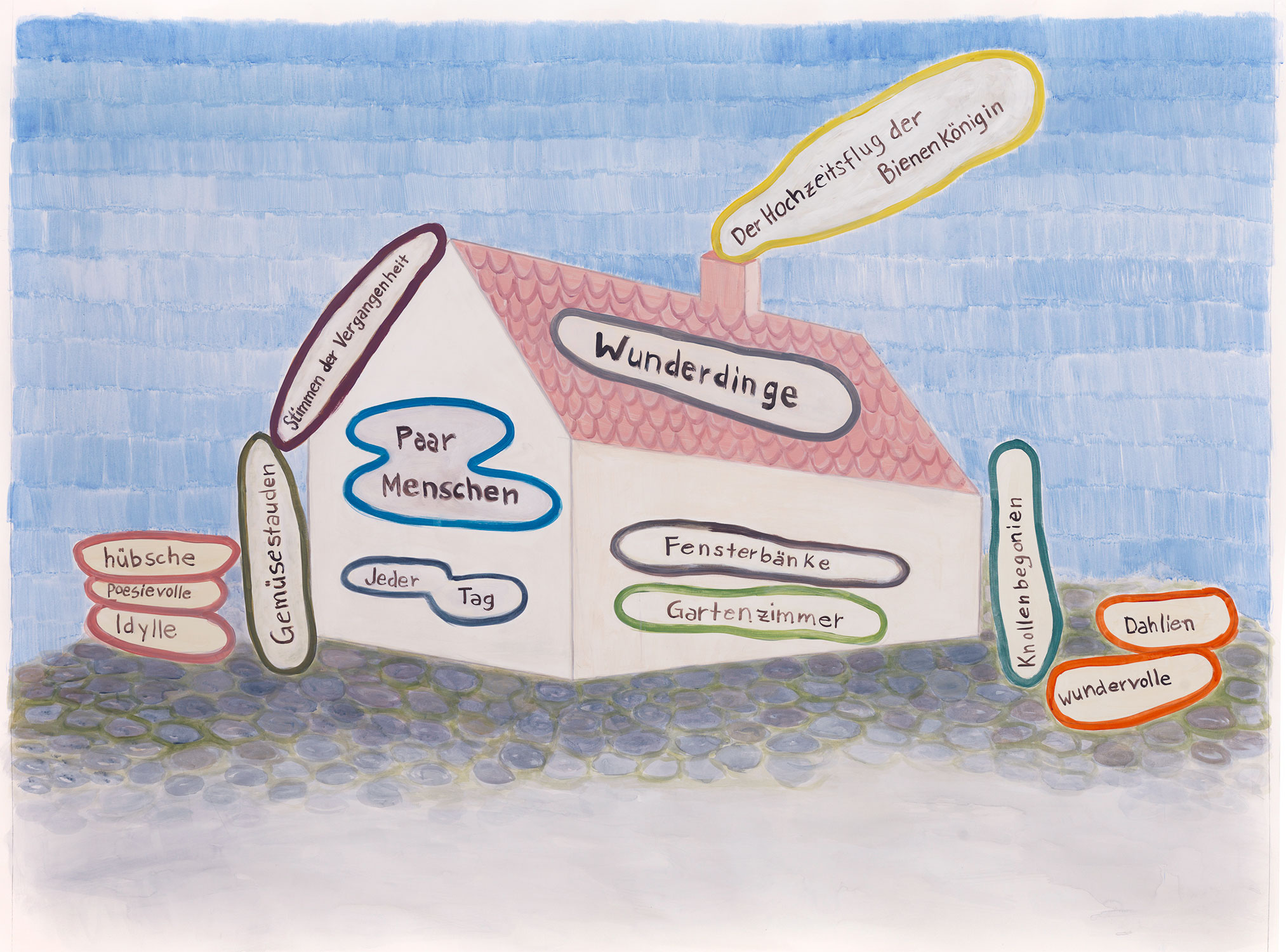

Image and text each form a space on their own By combining and shaping them with different materials and techniques, I create a new, imaginary space. This is a recurring element in my work. Its content is influenced by personal experiences and the language and culture I grew up with.

Bringing reality to a hold

Life, and the way in which it is influenced by culture from the day we are born, is special. A child will experience that a house offers shelter and language clarity. And thus the process of socialisation continues, like a self-strengthening faith. But unlike with unconditional faith, questions arise from early on. The moment a child is able to ask questions, it is also able to consider options other than the ones it is offered. This is the moment that the dormant imagination awakens. The ongoing cycle of questioning and accepting continues amongst other things in science and – of course – art. Through questioning acceptance, reality is brought to a hold and revised. This can result in a completely different perception of reality, and sometimes imagination and actual reality collide. This creates the absurd.